from IPython.core.display import HTML

def _set_css_style(css_file_path):

"""

Read the custom CSS file and load it into Jupyter.

Pass the file path to the CSS file.

"""

styles = open(css_file_path, "r").read()

s = '<style>%s</style>' % styles

return HTML(s)

_set_css_style('rise.css')

Sequence analysis and biopython¶

- Sequence data and formats

- Sequence objects in Biopython

- Sequence search

- Alignment objects in Biopython

FASTA¶

First line is description of sequence and starts with >

All lines up to the next > are part of the same sequence

Usually less than 80 characters per line

>gi|568815581:c4949086-4945650 Homo sapiens chromosome 17, GRCh38.p2 Primary Assembly

CCCGCAGGGTCCACACGGGTCGGGCCGGGCGCGCTCCCGTGCAGCCGGCTCCGGCCCCGACCGCCCCATG

CACTCCCGGCCCCGGCGCAGGCGCAGGCGCGGGCACACGCGCCGCCGCCCGCCGGTCCTTCCCTTCGGCG

GAGGTGGGGGAAGGAGGAGTCATCCCGTTTAACCCTGGGCTCCCCGAACTCTCCTTAATTTGCTAAATTT

GCAGCTTGCTAATTCCTCCTGCTTTCTCCTTCCTTCCTTCTTCTGGCTCACTCCCTGCCCCGATACCAAA

GTCTGGTTTATATTCAGTGCAAATTGGAGCAAACCCTACCCTTCACCTCTCTCCCGCCACCCCCCATCCT

TCTGCATTGCTTTCCATCGAACTCTGCAAATTTTGCAATAGGGGGAGGGATTTTTAAAATTGCATTTGCA

Genbank¶

Annotated format. Starts with LOCUS field. Can have several other annotation (e.g. KEYWORDS, SOURCE, REFERENCE, FEATURES).

ORIGIN record indicates start of sequence

'\\' indicates the end of sequence

LOCUS CAG28598 140 aa linear PRI 16-OCT-2008

DEFINITION PFN1, partial [Homo sapiens].

ACCESSION CAG28598

VERSION CAG28598.1 GI:47115277

DBSOURCE embl accession CR407670.1

KEYWORDS .

SOURCE Homo sapiens (human)

ORGANISM Homo sapiens

Eukaryota; Metazoa; Chordata; Craniata; Vertebrata; Euteleostomi;

Mammalia; Eutheria; Euarchontoglires; Primates; Haplorrhini;

Catarrhini; Hominidae; Homo.

ORIGIN

1 magwnayidn lmadgtcqda aivgykdsps vwaavpgktf vnitpaevgv lvgkdrssfy

61 vngltlggqk csvirdsllq dgefsmdlrt kstggaptfn vtvtktdktl vllmgkegvh

121 gglinkkcye mashlrrsqy

//

Biopython¶

Biopython features include parsers for bioinformatics file formats (BLAST, Clustalw, FASTA, Genbank,...), access to online services (NCBI, Expasy,...), interfaces to common and not-so-common programs (Clustalw, DSSP, MSMS...), a standard sequence class, various clustering modules, a KD tree data structure, and even documentation.

Other modules that might be of interest:

- Pycogent: http://pycogent.org/

- bx-python: http://bitbucket.org/james_taylor/bx-python/wiki/Home

- DendroPy: http://packages.python.org/DendroPy/

- Pygr: http://code.google.com/p/pygr/

- bioservices: https://bioservices.readthedocs.io/en/master/

Biopython is not for performing sequencing itself (see: Pitt CRC workshops).

Sequence Objects¶

from Bio.Seq import Seq # the submodule structure of biopython is a little awkward

s = Seq('GATTACA')

s

Sequences act a lot like strings, but have additional methods

Methods shared with str: count, endswith, find, lower, lstrip, rfind, split, startswith, strip, upper

Seq methods:back_transcribe, complement, reverse_complement, tomutable, tostring, transcribe, translate, ungap

Accessing Seq data¶

Sequences act like strings (indexed from 0)

s[0]

s[2:4] # returns sequence

s.lower()

s + s

The Central Dogma¶

DNA coding strand (aka Crick strand, strand +1)

5’ ATGGCCATTGTAATGGGCCGCTGAAAGGGTGCCCGATAG 3’

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

3’ TACCGGTAACATTACCCGGCGACTTTCCCACGGGCTATC 5’

DNA template strand (aka Watson strand, strand −1)

|

Transcription

↓

5’ AUGGCCAUUGUAAUGGGCCGCUGAAAGGGUGCCCGAUAG 3’

Single stranded messenger RNA

|

Translation

↓

MAIVMGR*KGAR*

amino acid sequence (w/stop codons)

dna = Seq('GATTACAGATTACAGATTACA')

dna.complement(),dna.reverse_complement()

The Central Dogma¶

dna

rna = dna.transcribe()

rna

protein = rna.translate()

protein

dna.translate() # unlike cells, don't actually need rna

Codon Tables¶

By default the standard translation table is used, but others can be provided to the translate method.

from Bio.Data import CodonTable

print(sorted(CodonTable.unambiguous_dna_by_name.keys()))

print(CodonTable.unambiguous_dna_by_name['Standard'])

SeqRecord¶

Sequence data is read/written as SeqRecord objects.

These objects store additional information about the sequence (name, id, description, features)

SeqIO reads sequence records:

- must specify format

readto read a file with a single recordparseto iterate over file with mulitple records

from Bio.SeqRecord import SeqRecord

from Bio import SeqIO

seq = SeqIO.read('../files/p53.gb','genbank')

seq

seqs = []

# https://MSCBIO2025-2024.github.io/files/hydra.fasta

for s in SeqIO.parse('../files/hydra.fasta','fasta'):

seqs.append(s)

len(seqs)

Fetching sequences from the Internet¶

Biopython provides and interface to the NCBI "Entrez" search engine

The results of internet queries are returned as file-like objects

from Bio import Entrez

Entrez.email = 'jpbarton@pitt.edu' # biopython forces you to provide your email

res = Entrez.read(Entrez.einfo()) # the names of all available databases

res

print(sorted(res['DbList']))

ESearch¶

You can search any database for a given term and it will return the ids of all the relevant records

result = Entrez.esearch(db='nucleotide', term='tp53') # the result is a file-like object of the raw xml data

records = Entrez.read(result) # put into a more palatable form (dictionary)

print(records)

There were many hits, but by default only 20 are returned

We can change this (and other parameters) by changing our search terms

records = Entrez.read(Entrez.esearch(db='nucleotide', term='tp53', retmax=50))

records

EFetch¶

To get the full record for a given id, use efetch.

Must provide rettype (available options include fasta and gb)

retmode can be text or xml

#fetch the genbank file for the first id from our search

result = Entrez.efetch(db="nucleotide",id=records['IdList'][0],rettype="gb",retmode='text')

#parse into a seqrecord

p53 = SeqIO.read(result,'gb')

result

p53

Features¶

Genbank files are typically annotated with features, which refer to portions of the full sequence

SeqRecord objects track these features and you can extract the corresponding subsequence

CDS - coding sequence

p53.features

Extracting subsequences¶

cdsfeature = p53.features[3]

print(cdsfeature)

The subsequence the feature refers to can be extracted from the original full sequence using the feature.

coding = cdsfeature.extract(p53) #pass the full record (p53) to the feature

coding

BLAST¶

Biopython let's you use NCBI's BLAST to search for similar sequences with qblast which has three required arguments:

- program: blastn, blastp, blastx, tblastn, tblastx

- database: see website

- sequence: a sequence object

BLAST uses a heuristic approximation of the Smith-Waterman pairwise sequence alignment algorithm

from Bio.Blast import NCBIWWW

result = NCBIWWW.qblast('blastn','nt',coding.seq,hitlist_size=250)

# result is a file-like object with xml in it - it can take a while to get results

from Bio.Blast import NCBIXML #for parsing xmls

blast_records = NCBIXML.read(result)

print(len(blast_records.alignments),len(blast_records.descriptions))

alignment = blast_records.alignments[0]

print(len(alignment.hsps))

hsp = alignment.hsps[0] # high scoring segment pairs

print('****Alignment****')

print('sequence:', alignment.title)

print('length:', alignment.length)

print('e value:', hsp.expect)

print(hsp.query[0:75] + '...') # what we searched with

print(hsp.match[0:75] + '...')

print(hsp.sbjct[0:75] + '...') # what we matched to

alignment = blast_records.alignments[-1] # get last alignment

hsp = alignment.hsps[0]

print('****Alignment****')

print('sequence:', alignment.title)

print('length:', alignment.length)

print('e value:', hsp.expect)

print(hsp.query[0:75] + '...') # what we searched with

print(hsp.match[0:75] + '...')

print(hsp.sbjct[0:75] + '...') # what we matched to

Alignments¶

AlignIO is used to read alignment files (must provide format)

from Bio import AlignIO

align = AlignIO.read('../files/hydra179.aln','clustal')

align

print(align)

Slicing Alignments¶

Alignments are sliced just like numpy arrays

align[0] # first row

align[:,0] # first column

print(align[:,0:10])

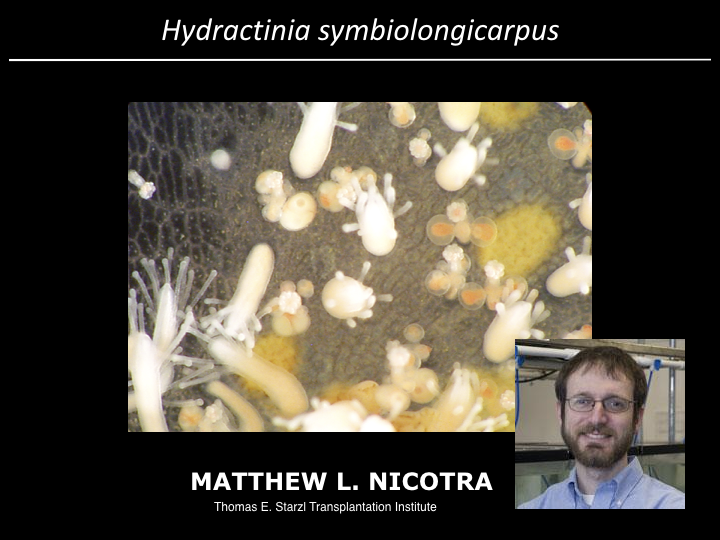

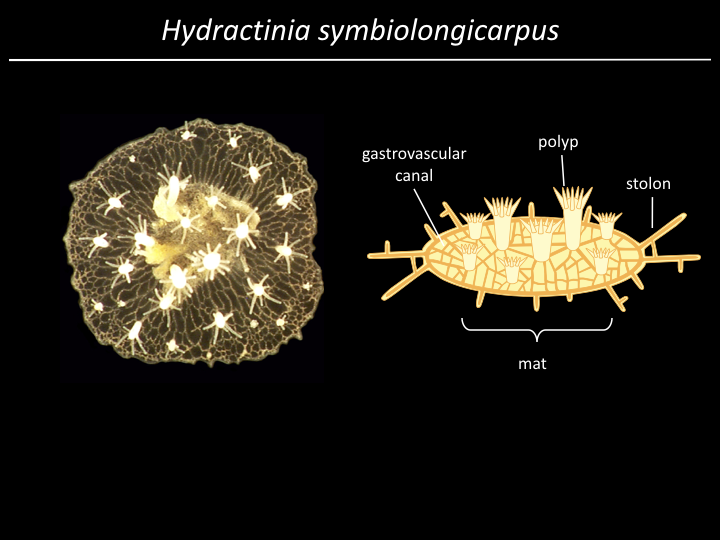

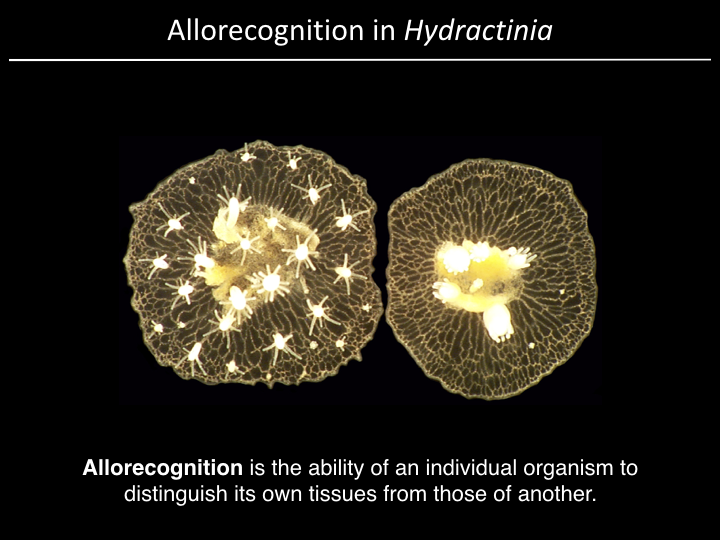

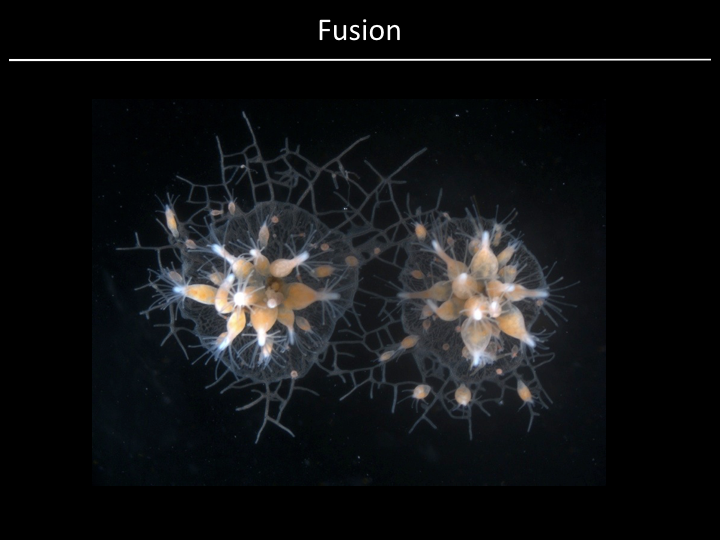

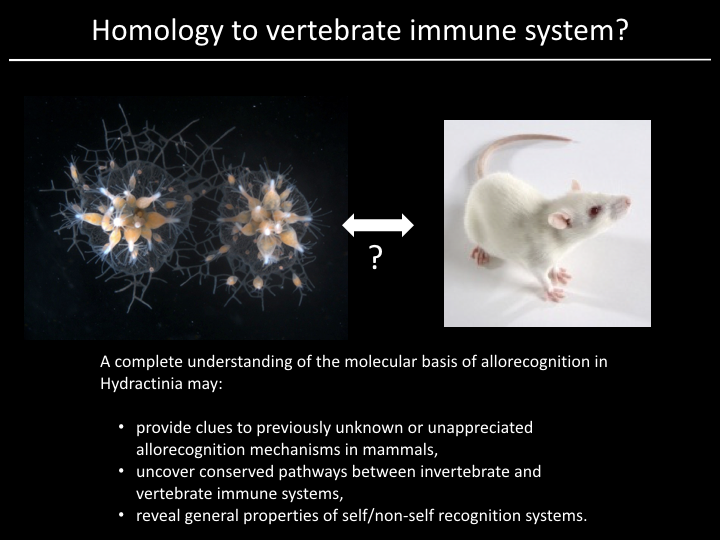

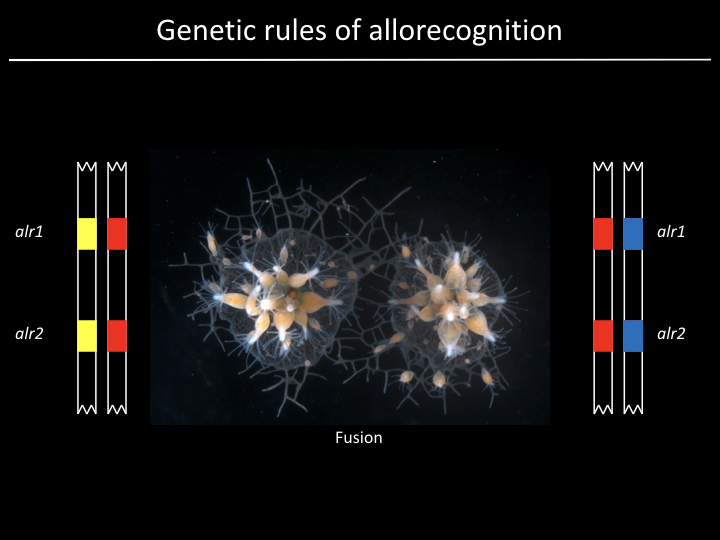

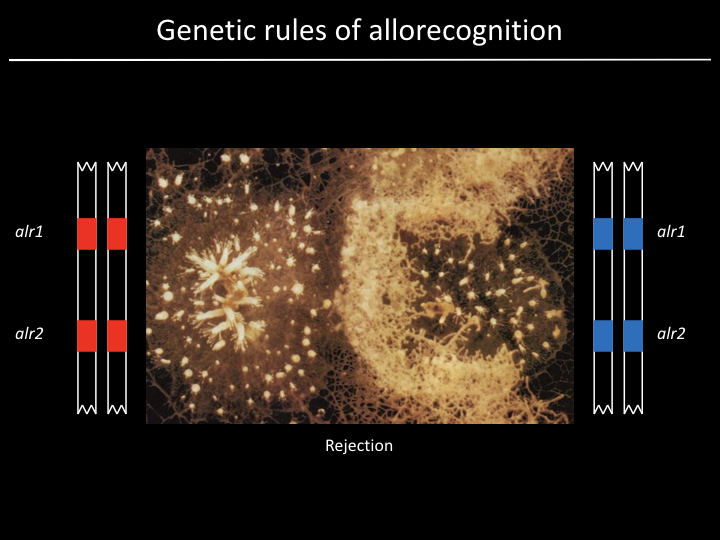

And now for a brief foray into marine microbiology...¶

Project¶

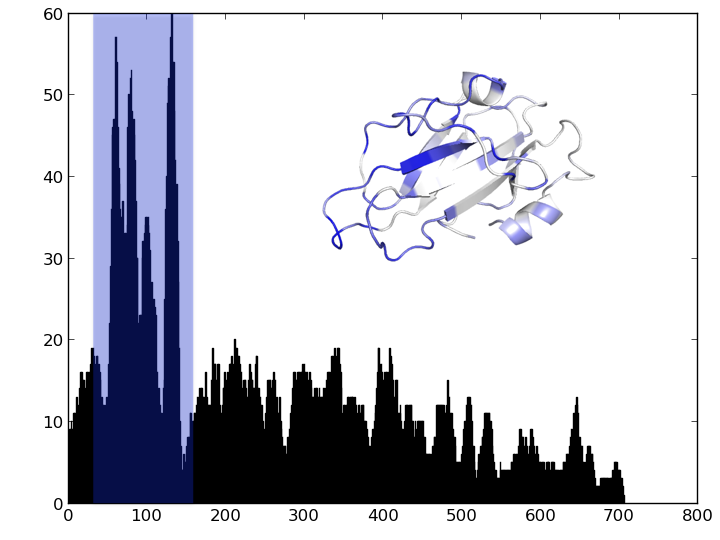

We have a gene (alr2), but what part of the gene is responsible for allorecognition?

Given 179 sequences, how might we find out?

Find the part of the sequence that changes the most

- Count number of distinct residues at each position and plot

- Count number of distinct subsequences of length 10 at each position and plot

For next time¶

More sequence analysis!

Phyolgenetic trees, sequence motifs, and list comprehensions